If you’ve been a Peloton member for any length of time, you probably have been hearing about “calibration”. Not from Peloton, no. They hardly ever mention it. It is a topic in social media, though, and it seems that there is a widespread problem that Peloton may have no way of getting on top of. Potentially a couple hundred thousand of these bikes are essentially out of whack, and there’s no obvious fix.

What is meant by “calibration”?

Calibration, broadly, relates to the data coming back from the equipment that is used (either directly or as part of a calculation) to give the rider feedback on his or her efforts. Calibration could involve the measurements of cadence, heart rate, etc., but when you hear “Peloton” and “calibration” in the same sentence, it is the bike’s resistance that is the topic.

If you need a quick refresher on cadence, resistance, and the other Peloton metrics, click over to this explanation of Peloton cadence, resistance, and output.

Resistance is the measurement of how difficult it is to turn the Peloton flywheel, and is displayed as a percentage. You’d think that this would be essentially linear, with 0 being no resistance and 100 being complete resistance, and that 50 resistance is twice as strong as 25 resistance. If that were the case, this would be a fairly short post.

Resistance, the mystery metric

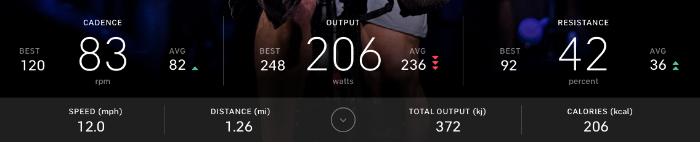

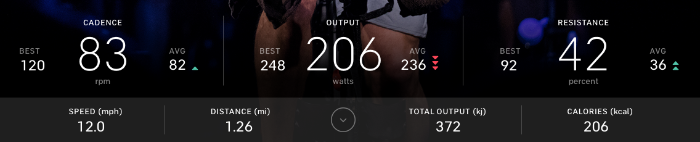

What’s really important to understand is that resistance is at the heart of pretty much everything else that is measured (besides time and heart rate). I’m speaking specifically of power generated (watts), work done (kilojoules) and calories burned. These metrics (particularly the second) are the means by which Peloton riders compare themselves to one another. If resistance is not accurate, then there isn’t much left in the metrics you can trust.

So, how reliable is the resistance number? That is the million dollar question. There is evidence to suggest that some bike’s resistance numbers are questionable. In fact, there is far more evidence to show that bikes’ resistance numbers vary greatly than there is evidence that there is any uniformity to resistance at all.

Exhibit A: Social media posts in which people talk about how challenging a ride based on how many times they got to 100 resistance. Now, by definition, 100% resistance means that the wheel is completely resisted. That is, it cannot be turned. If it can be turned, then it is by definition not fully resisted. Yet notice the results graph in the accompanying photo in which the rider apparently rides for two minutes at 100% (and then proceeds to exceed 100%, at which point I guess the bike should actually be forcing your pedals backwards, or something).

There are many anecdotes about broken bikes that show 100% regardless of how much resistance is actually added, but it’s probably safe to assume that they are a pretty small minority. If, however, there are some percentage of bikes that people can pedal at 100% resistance (with difficulty, as the proud social media posters note), it begs the question of whether your 100% resistance is the same as my 100% resistance.

Giving %110

It’s like the koan-like question: how can we be sure that when I see the color “blue”, the color I see isn’t the one that you’d call “red”? I know something is blue because it is the same color as other things that I also identify as blue. But I have never seen anything with your eyes, and I have no idea what the color blue looks like to you. I only know that something is blue because I compare it to other things I call blue, and things are only more or less blue compared to my internal frame of reference.

We face the same dilemma when it comes to resistance. Compared to the color example, it is a bit easier (but not so easy) for me to determine if your 40% resistance is the same as my 40% resistance. If it’s wildly different, then I can perceive of the difference, but if it’s close, then it’s not likely I’d be able to discriminate, say, between a few percentage points.

Resistance is futile at the Peloton mothership

I have personally ridden on about five Peloton bikes, and I’d have to say that the ones I rode in the Peloton store, my own bike at home, and my brother’s bike all felt about the same to me. The bike I rode in the Peloton studio, on the other hand, was conspicuously easier than any of the others. Yes, maybe I was pumped up for the ride at the Mothership (SO to JJ!), but I don’t think that accounts for the difference. The PRs I set that day still stand, and my next best effort isn’t close. Although I have no data to back it up, I am convinced that the bike at the Peloton studio was the “easiest” bike I’ve ridden.

This is where “calibration” comes in

This all comes back to “calibration”. Calibration is the act of accurately setting the measuring devices, and in the case of these bikes, is performed at the factory. Presumably, there can be some change over time (“drift” is what it’s called) or calibration could be affected by jostling that occurs during the delivery and installation of your bike, so the calibration tools are included with your bike when it is delivered to you. (Anybody have their bike calibrated by the installers? Didn’t think so. Anybody want those guys making adjustments on your bike? Didn’t think so.) I won’t go into the specifics of calibration, but you can do an internet search to find Peloton’s own instructional video. I’ve been through the video and, in my humble opinion, their process still includes a fair bit of subjectivity that could lead to variations even across “calibrated” bikes.

So, how do you trust that the resistance numbers (and, by extension, the all-important output numbers) are the same from bike to bike? This would seem to be nearly impossible to know. To accurately determine if the amount of effort needed to turn one bike’s flywheel is equal to the effort required for another bike one would need additional equipment, such as replacement crank arms or pedals with power meters built-in. Of course, THOSE devices would need to be calibrated, too!

As it is, I don’t believe anyone has an accurate picture of the amount of variability there are in the power calculations across bikes, and I don’t believe there is really any way that Peloton could measure and correct for this, even if they wanted to.

The good news is that if you bear in mind that your true competitor is yourself, then none of this should really matter. Your own bike’s resistance calibration is not likely to drift significantly over time, so if you are now cranking out 30% more KJs this year over last, you can be pretty sure you’ve made some serious progress.

As for me, I just assume that anyone ahead of me on the leaderboard needs to get their bikes calibrated.

— #LeftShark

or…. My trip to the Mothership

or…. My trip to the Mothership

I could be wrong about that, but this impression was reinforced by the one other rider that I did chat up while I was there. I made the acquaintance of Joe who, as far as I could tell, was the only other person doing the morning classes back-to-back. Joe told me he lived fairly close by, and didn’t really seem to me to be into the Peloton culture — he was just there to get some exercise. He did know all of the other gyms and competing exercise venues in the area. All in all a pretty pleasant guy, but not really what I thought I was going to find.

I could be wrong about that, but this impression was reinforced by the one other rider that I did chat up while I was there. I made the acquaintance of Joe who, as far as I could tell, was the only other person doing the morning classes back-to-back. Joe told me he lived fairly close by, and didn’t really seem to me to be into the Peloton culture — he was just there to get some exercise. He did know all of the other gyms and competing exercise venues in the area. All in all a pretty pleasant guy, but not really what I thought I was going to find. Recently, a Peloton rider posted an

Recently, a Peloton rider posted an